The Core Contributors want Translate Science to be a community of interest around the broad issues concerning multilingualism in science. To achieve this we hope that by amplifying diverse ideas and experiences via the medium of an online panel discussion we can help others understand how they too may have important perspectives to share. Our intention is to maintain a conversation that connects folks across disciplines so they can better advocate for multilingual science from their positions.

On September 3rd we had our second panel with 2 wonderful guests: Humberto Debat (tenured Research Scientists, Institute of Plant Pathology Center for Agricultural Research, Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria) and Devang Mehta (tenure-track Assistant Professor, Department of Biosystems, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven). We invited Devang because one of our core contributors Carolina Quezada worked with him through the ecrLife editorial team where they used the platform to draw attention to issues in research culture. Humberto was invited by searching our mailing list for candidates and we thought their work on PanLingua was very aligned with Translate Science.

We used the same questions from our first panel as a starting point to get our discussion going:

- What is your role in the world of science?

- How do you bring open science values into your role?

- How do you bring multilingualism into your role?

Below is a summary of the discussion.

Humberto was born, raised, and educated in the province of Cordoba, Argentina. Spanish is his first language and although he uses English frequently in the course of his international work he feels his skill in this second language is far outstripped by his ability to communicate in Spanish. He states that working in English is a privilege as only about 6% of Argentinians speak English and this presents a barrier to some of his colleagues getting visibility and recognition of their work. His institution, the Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria (INTA), is a federal agency that pursues a research agenda set by the needs of the country’s agricultural sector. INTA requires that researchers’ work and the implications of it to be reported in Spanish. It is here that Humberto applies his skills in virology to study disease in local crops.

Publishing incentives are different for Humberto than that of an academic based at a university. He explains that INTA’s institutional repository is the main place where his research outputs are deposited and 70% of this archive is in Spanish to ensure that implications of the work there can be understood by local colleagues and stakeholders. Interpreting the Argentine Nobel laureate Bernardo Houssay’s words (who may have been inspired by Pasteur’s words many years earlier) “science has no homeland, but the scientist does”, Humberto says he sees research as a global conversion, but he applies it towards a local agenda. He aspires to be able to conduct research in a more participatory fashion where populations in need of formal knowledge are included in the design and process of knowledge generation. However, such participation must be able to reconcile the colonial tensions that come baked into the language used to do such outreach.

Humberto became aware of a large gap between the state of thought in the sociolinguistic field versus the biomedical field concerning the politics of language used in scholarly communications when he attended a conference on that topic. There he learned about an article titled “Rethinking English as a lingua franca in scientific-academic contexts: A position statement” explaining that “[the article] talks a lot of the inequities that derive from the [claim] which appears to be common sense but is a political thing to [accept]: English as a lingua franca in scholarly communications”. He continues to elaborate that accepting this claim has implications for “the directionality of knowledge, dissertation structures, the privilege of English in the research evaluation and assessment system; and how it affects the identity of the generators of knowledge.” Humberto wants to increase the awareness of this power dynamic and develop solutions for these issues. He says “English is a choice—perhaps a useful choice—but it has a lot of baggage with it” and wants to decouple the narrative aspect of science from its other elements.

Devang grew up in Mumbai, India. He studied biotechnology in the south of India and then pursued a Masters in the UK, PhD in Switzerland, Post-Doc in Canada, and finally settled in Belgium where he is starting his own lab studying the circadian rhythms in plants. Devang’s education has been primarily in English but the languages spoken in everyday life around him have varied greatly. His current institution mandates research duties as well as teaching in the Masters program. Teaching in this program occurs in English—a second language for the Dutch-speaking student population—in contrast to the undergraduate instruction that is performed in Dutch. Devang must reach the B2 level in Dutch as a requirement for tenure as part of a government regulation. While the course work for this requirement was offered for free by his institution he spent many weeks studying Dutch that, in his words, “takes a lot of time away from my research, from writing grants, from writing papers; and that is not something that my employer has, you know, given me an extra grant or something like that. So there are some sacrifices involved in having to learn the language”.

Devang helps bioArxiv process preprints and was a member of the Early Career Advisory Group at eLife, a publication that promotes open science. He stresses that “there are things we can do in community and as individuals” to promote open science. His lab group has publicly pledged to publishing only outside of for-profit journals and are encouraging their collaborators to do the same. Devang’s group publishes in English and the university issues press releases in both English and Dutch. Interpretation is used when required to interface with local journalists as well as coverage from other European language communities.

In India, where there are 23 official languages, there is a push for proactive science outreach to be done in local languages. This means new coverage of research might be done in English, Hindi, and a local language. Devang has observed that India seems quite capable and willing to tackle their linguistic barriers while in Belgium the willingness and infrastructure to bridge between French and Dutch speaking communities is less developed. He points out that language is a contentious political topic in Belgium and there is a border between the Dutch and French speaking areas. In his experience, the imposition of rules dictating a preferred language doesn’t help with communication. Devang recalls that, at a DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion) brainstorm between KU faculty, a major point was a desire to have more English used in communications.

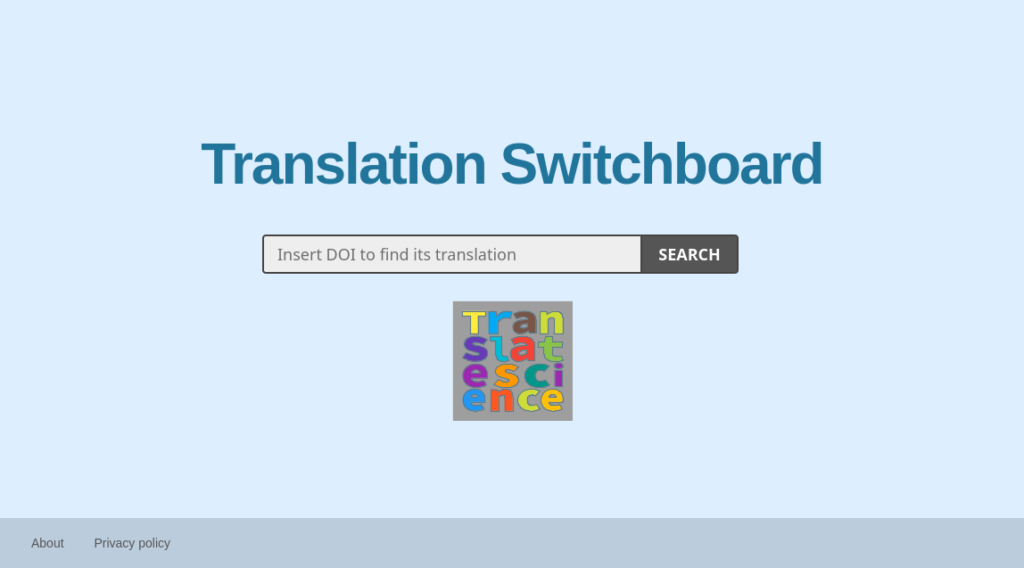

Both panelists use machine translation to help with their day-to-day work. They express a hope and desire for a future where these tools work better than they currently do. On this topic our audience and one of the panelists have a cautious perspective to share in their capacity as translators: existing tools are probably at their peak, and improvements for fields and languages which do not work will probably be very costly.

We think this quote from Devang wraps up our summary well: “We need to keep moving towards a world—at least in science—where we stop being so focused on how perfectly you speak a language because often that in itself discourages people from even trying to speak English or Dutch or French or whatever the language is… The point of language is to communicate; if you get each others’ meaning the jobs done, the language has done its job”.

We hope you enjoy our summary and (re-)watching the video of our discussion and invite you to join our next online panel discussion! If you have ideas of potential panelists or would like to contribute yourself, please reach out by email to info@translatescience.org.

Sign up for our mailing list to stay informed on our activities!