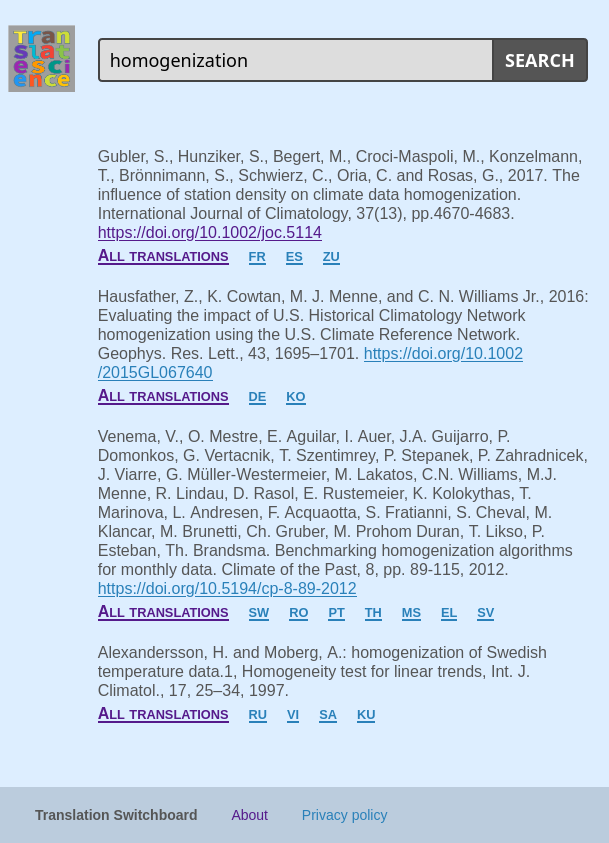

You know an article exists, but cannot read its language. So you go to our tool, paste the Digital Object Identifier of the article and get a list with translated versions. You manage your articles in a reference manager and notice that an article on your reading list is now also available in your mother tongue. You are really enthusiastic about a new article that was just published, which has policy implications for your country and you want to translate it so that more people can read it, on our tool you find a partial translation made by a colleague from another university department; you jointly finish the translation, publish it on a repository and upload the link to our database.

These scenarios demonstrate that a translation finding tool would be really useful and could also stimulate the production of translations.

One of us started dreaming of such a tool attending a climate conference in Peru. Colleagues from the local weather service were doing interesting work, but many did not speak much English. An important way they kept up to date were the guidance reports written by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), one of the oldest open science organizations. They translate all their guidance reports into many languages because the weather services who control the WMO see this as a priority. A colleague at the conference told me that she sometimes translates important English articles into Spanish and emails them to her colleagues; just like Albert Einstein translated important studies into English. That made me wonder whether we could spread translations in a better way and thus also stimulate their production.

Lingua Franca

Translations are part of the open science movement. Translated scientific articles make science more accessible to regular people, science enthusiasts, activists, advisors, trainers, consultants, architects, doctors, journalists, planners, administrators, technicians and many scientists.

English as a common language has mostly made global communication within science easier. However, this has made communication with non-English communities harder. This goes both ways, people who could benefit from scientific knowledge and people who have knowledge scientists should know.

For English-speakers it is easy to overestimate how many people speak English because we mostly deal with foreigners who do speak English. However, it is thought that that only about one billion people speak English. That means that seven billion people do not.

Translated scientific articles speed up scientific progress by tapping into more knowledge and avoiding double work. They thus improve the quality of science. The additional two-way knowledge transfer aids innovation and tackling the big global challenges in the fields of climate change, agriculture and health. Translations can improve public disclosure, scientific engagement and science literacy.

Open Source tool

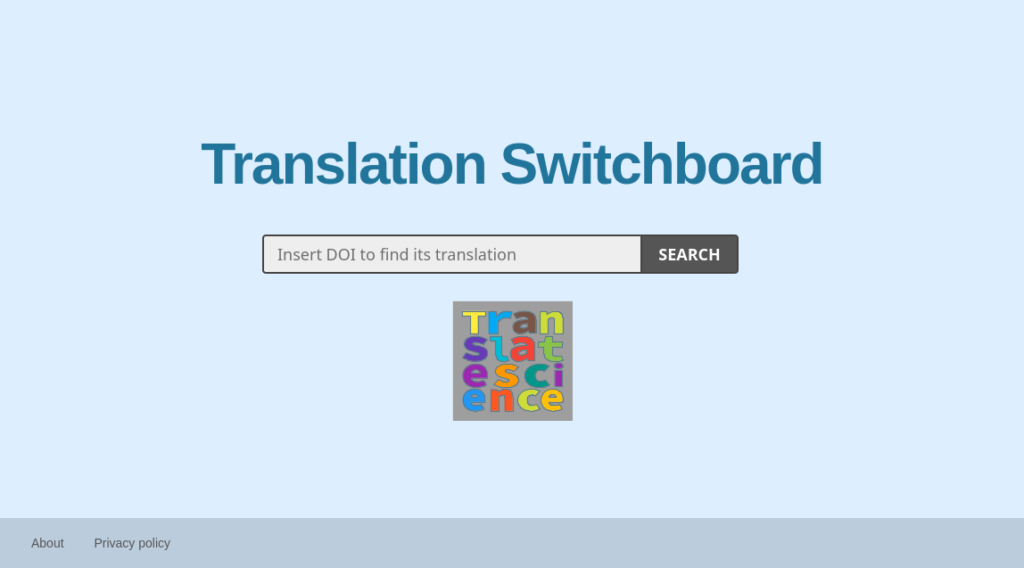

We want to develop and deploy an open source tool to make it easier to find translations and thus make them more worthwhile to make. In its simplest form people should be able to search using a Digital Object Identifier, a title or the names of the authors and be presented with a list with links to translations. People or organizations who made or have translations should be able to upload lists with links. Users and volunteers should be given moderation tools.

Also searching by topic and a topic directory would be useful as translated articles tend to be the more important ones in a field. The database should also be accessible via an Application Programming Interface (API) so that other tools and webpages can automatically display information on any translations and inform us about new translations.

People or organizations who made or have translations should be able to upload lists with links. There were similar databases during the Cold War to keep up with Soviet research and we want to try to rescue their datasets and upload them to our database. Many research libraries, international organizations and research institutes (World Meteorological Organization, UK Met Office, …) have translated articles and reports, which should be included. Also translations of articles written before English was the Lingua Franca.

The expensive organizations maintaining these databases and making translations collapsed after the Cold War. In the internet age, we can maintain large knowledge bases cost effectively with global volunteers, as Wikipedia has demonstrated, and include many more languages. Also translating has become much easier as a reasonable first draft can often be provided by machine learning. And we can now network people who only occasionally make translations (of their own articles).

Not every contribution will be perfect. Users and editors of such a database should be be able to indicate how good a translation is and need moderation tools. With versioning it should be easy to revert vandalism or spamming. We could green lists known scientific repositories and red lists known spammers.

If there are multiple translations for a language, editors or users should be able to rank them and indicate which one is best. If only because external systems using our information may be designed to only accept one translation per language as that will be the most typical case.

A “talk page”, similar to Wikipedia’s, could be useful to allow users to point to problems, discuss which translations are best and which quality flags need to be set. Possibly even to organize to jointly make a better translation. This could be implemented with a commenting or forum system in a background tab.

Copying the idea of Wikipedia of making a page with recent changes can help with quality control. Such a page can be filtered in several ways, e.g., for contributions by new people. In case someone finds that a participant made a problematic contribution a look at their user pages may find more problems.

Many more technical details of how such a system could look can be found on our Wiki.

Points to ponder

How hard would it be to make the system distributed, to have multiple servers who talk to each other and exchange data if they trust each other? We are doing this for science, but there are groups outside of science who could use similar system; the nearest to us would be education and science communication. (Disciplinary) groups within science may be able to use their networks to promote the production of translations. That would make bulk download of our data a good idea to get a new server started.

It could be worthwhile to make a (private) backup of the known translations and regularly check for broken links. The backup can help the editors find the new location of the translation or to upload it elsewhere if the license allows for this.

It may be a good idea to have multiple types of links to translations. Literal translations, but also related works in another language, for example a PhD thesis in language X and a corresponding article in language Y. Sometimes people may write a summary of an article in another language, which could be valuable if there is no full translation. Also links to partial translations can still be valuable and showing them could promote their completion.

The road ahead

The above mainly describes the technical aspects of such a Translations Switchboard, but there is also a human aspect. We will need a community of editors for every language to check submitted URLs to avoid spam and select the best version in case multiple ones are available. So we need tools to build and organize this community. We will also need publicity so that people know about the service. Part of the advertising could function via integration of our system in others. We will need volunteers who contact possible sources of translations which could be integrated into the database and to promote the production of translations in their circles.

Designing and coding the full system described above would be a considerable task. If someone has experience with similar projects and would like to apply for funding: feel free to make the idea your own; we are also happy to be the science advisory team. For now we decided to start small. Create a minimal system and add the data we know of to it. That way the idea becomes more concrete, which will hopefully help to find resources to build it and to fill the database. This first version will be coded using PHP, HTML, CSS and Maria DB.

You can already help us a lot by spreading this idea to increase the chance that people interested in contributing learn out it. Also feedback on the idea in the comments below is very valuable. If any of the above appeals to you, please get in touch on Mastodon or by email.