In case you might not yet have had a chance to read this previous blog post by my colleague please do so, it accurately addresses the well-known dilemma faced in the current scholarly publishing landscape in science.

About 2000 languages are spoken in Africa, and these traditional and indigenous dialects are also a medium of choice in knowledge dissemination for many scientists on and off the continent.

As pointed out in the earlier mentioned blog post, many African scientists are proficient in the English language and regularly publish their scholarly communications in Anglophone. In 2018 alone AfricArXiv preprint repository scholarly African collection had 25 submissions in English.

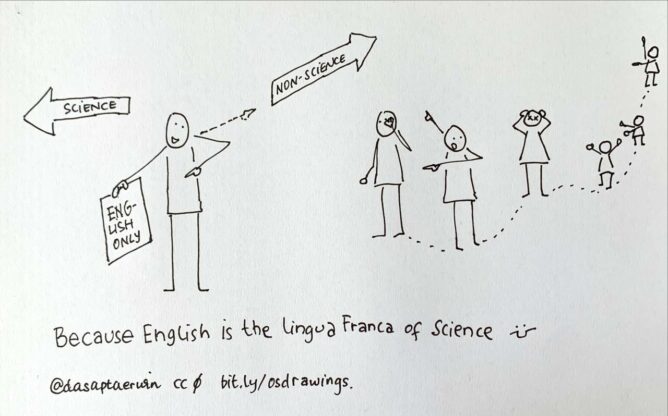

It is however not lost on such scholars, myself included, that whereas we are multilingual, we face unilingual constraints in expressing our mostly written publications as well as sometimes in our spoken word presentations.

I believe that technology in its role as an enabler of positive change could play a vital role in bridging this gap through the use of Artificial Intelligence (A.I.) offering a service of providing a seamless translation platform for scientific work written in different official African languages.

One of the key task for such an A.I. system could be accepting English-papers written by African researchers and offering a seamless translation service resulting in the output of as many African languages as possible, and vice versa, and in a manner that is structured to build on previous learning.

To quote my colleague in the previous blog post “With the advancement of Natural Language Processing (NLP), it should be fairly easy for non-Indonesian [or African] speakers to understand articles written in Indonesian [or African local dialects]. Hence the burden to immediately use English as the main language of science could be lowered.”